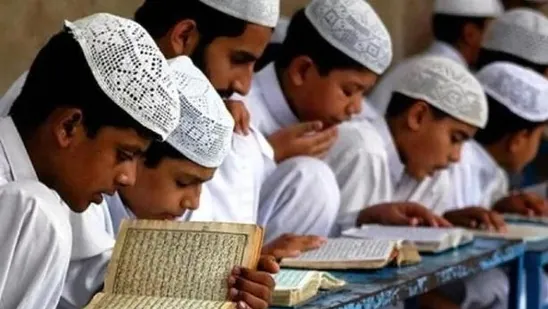

The crucial responsibility of the UP government in aligning educational standards in madrasas with modern academic expectations was emphasized by the Supreme Court.

The decision of the Supreme Court invalidated the ruling made by the Allahabad High Court in March regarding the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act.

The Uttar Pradesh Madarsa Education Act’s Legitimacy: The Supreme Court overturned the Allahabad High Court’s ruling in March, which deemed the 2004 Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act as unconstitutional.

The Uttar Pradesh government was highlighted by a bench led by Chief Justice of India (CJI) DY Chandrachud, alongside Justices JB Pardiwala and Manoj Misra, for its crucial responsibility in aligning educational standards in madrasas with contemporary academic norms. The bench suggested transferring students to alternate schools as a solution.

According to the Supreme Court ruling, madrasas are prohibited from awarding higher education degrees as it goes against the University Grants Commission Act.

The Chief Justice of India stated during the verdict announcement that the UP madrassa law’s validity has been maintained, emphasizing that a statute can only be invalidated if the state lacks legislative competence.

The Supreme Court stated that the legislative framework of the UP Board of Madarsa Education Act aimed to standardize the educational standards set for madrasas.

On October 22, the bench deferred its decision on eight petitions, which included the main one submitted by Anjum Kadari challenging the high court’s ruling.

Could you please provide me with another version to work on?

The Act was deemed “unconstitutional” and against the principle of secularism by the Allahabad high court on March 22. Consequently, the Uttar Pradesh government was directed to integrate madrasa students into the formal education system.

The verdict of the high court scrapping the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004, was temporarily halted by the CJI-led bench on April 5, providing relief to approximately 17 lakh madrasa students.

The Chief Justice of India remarked during the proceedings that secularism embodies the principle of allowing others to live freely.

DY Chandrachud stated that it was in the best interest of the nation to oversee madrasas, considering that segregating minorities into isolated communities could not erase centuries of the country’s diverse culture.

The Uttar Pradesh government affirmed its support for the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004 in answer to the bench’s inquiry, stating that it believed the Allahabad high court’s ruling declaring the entire law unconstitutional was unwarranted.

The Chief Justice of India concurred with senior lawyer Mukul Rohatgi, who represented the litigants challenging the high court’s decision, stating, “Secularism embodies the principle of coexistence.

The Chief Justice of India questioned the state government about the regulation of madrasas in relation to the composite national culture, emphasizing the importance of acting in the nation’s best interest.

The bench emphasized that disregarding several centuries of this nation’s history is not a feasible solution. If the high court order is upheld but parents continue sending their children to madrasas, it would result in isolated pockets without any legal measures in place. Inclusion through mainstreaming is the key to preventing ghettoization.

India was also requested to maintain its status as a melting pot of various cultures and religions.

The Chief Justice of India commented that religious teachings are not meant solely for Muslims, but for Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, and others as well. Emphasizing the importance of the country being a mosaic of various cultures, civilizations, and faiths, he advocated for its preservation in this manner. He suggested that the prevention of ghettoization lies in integrating people into mainstream society and promoting unity among them, rather than isolating them in separate communities.

The bench had questioned the validity of a law that acknowledged madrasas providing religious teachings, requiring them to adhere to specific standards. However, the complete repeal of the law resulted in these establishments being left uncontrolled.

The bench clarified that it did not want to be misconstrued, emphasizing its equal concern for ensuring quality education for madrasa students.

It expressed the view that nullifying the entire legislation equated to discarding something valuable along with something unnecessary, stressing that religious teachings have always been accepted in the nation.

The highest court listened to multiple attorneys representing the eight petitioners, along with additional solicitor general KM Natraj representing the Uttar Pradesh government, for approximately two days before finalizing the judgment.

Initiating the conclusive debates on the appeals challenging the decision, the panel also listened to seasoned attorneys such as Abhishek Manu Singhvi, Salman Khurshid, and Menaka Guruswamy representing the applicants.

Various litigants were represented by senior advocates Rohatgi, P Chidambaram, and Guru Krishna Kumar when they made their submissions.